I've just finished reading At The Deathbed of Darwinism. It's newly available on Project Gutenberg. It was publish in 1904, and was a collection of papers written by E. Dennert, Ph.D. I look at the work from an historic perspective. I'm not an historian, but have interests in how things are figured out, or not. It appears that many great ideas come from people with no significant standing. For an excellent example, see The Reminiscences of an Astronomer, by Simon Newcomb. And, a great many poor ideas come from people who one would think should have known better. This is one of those. It proves that anyone can get a doctorate. If you've wanted a doctorate - go for it. Remember, you heard it first here.

I've just finished reading At The Deathbed of Darwinism. It's newly available on Project Gutenberg. It was publish in 1904, and was a collection of papers written by E. Dennert, Ph.D. I look at the work from an historic perspective. I'm not an historian, but have interests in how things are figured out, or not. It appears that many great ideas come from people with no significant standing. For an excellent example, see The Reminiscences of an Astronomer, by Simon Newcomb. And, a great many poor ideas come from people who one would think should have known better. This is one of those. It proves that anyone can get a doctorate. If you've wanted a doctorate - go for it. Remember, you heard it first here.From the title, one might think that Darwinism is just about to vanish from scholarly thought. But over a hundred years have passed, heredity was being discovered, genetics was developed, tons of experimentation has been done, and the essential bits of Darwin's On the Origin of Species is still considered solid truth, more than ever. So what happened?

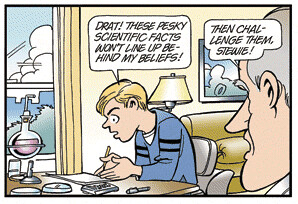

It's not that easy to pull it out. For one thing, this collection of papers rambles. The translation is excellent. Through it, you can still get the feeling of someone grasping at straws, any straws, to find evidence that supports the author's conclusions. And make no mistake, the conclusions were drawn first. Then the evidence is weighed. And, if the evidence does not support the conclusions, the evidence is downplayed, explained away, outright ignored, or out and out falsified. And pointlessly. But this isn't good science. It's non-science, which can be shortened to nonsense. And this is how the author argues. If it is too hard to argue with a speaker's ideas, then attack the character of the speaker.

The first question to answer is, what motivation does the author have? He spells it out. He considers Darwinism to be an affront, really an attack on Christianity. Why it is such an attack is hard to guess. The author is either silent, misleading or vague on this question. It could be because a literal interpretation of the Bible has God making the Universe in six days about 6,000 years ago. It could be because the author is uncomfortable with being related to apes, or even distantly related to slugs. Some of these things bother people today. They shouldn't. In particular, my own Christianity is completely compatible with the evolution of animals, including humans. It is completely compatible with the origin and evolution of the Universe. And, being related to slugs gives my life a connectedness to life on Earth, and a relationship with the Universe, in all it's glory. The ancient Biblical word translated as "day" could be as easily translated as "era" or "epoch", without a stated length. At that point, it is largely compatible with the Big Bang and Evolution models. And even if it wasn't, Genesis has moral lessons, like the fall from grace, and i never expected a history of the Universe.

The other bit about the book title has to do with the word Darwinism. Christianity is a belief system. The title, Darwinism, is not. One does not say "I believe in Darwinism". One might say, "Darwin's theory of natural selection is a powerful mechanism to explain the evidence". But if extraordinary evidence became available that suggested that Christ never existed, Christians would still be Christians. Yet if extraordinary evidence became available that showed that Darwin was wrong, scientists would drop it like a stone. That's because it isn't a belief system. That said, both Christianity and Science are attempts to learn truth. And truth is truth. Darwin's ideas weren't great because Darwin was a great man. Darwin was a great man because his ideas have stood the test of time.

E. Dennert, Ph.D. attempts to argue that natural selection doesn't work. He embraces all sorts of people who have ideas that might replace this concept. But it should be pointed out that these other ideas also support descent in general. That is, one species changes or branches into another. These ideas simply have other mechanisms. But natural selection, of itself, isn't the idea that is so offensive. Descent is. And this fundamental problem doesn't seem to be noticed in the text. And the flow of the ideas suffers from it. So the author dances around the problem. But in the end, you're left with the feeling that since Darwin introduced descent, he should be punished, and it doesn't matter how.

His first attack is a series of four questions.

1. Is there any evidence that such a struggle for life among mature forms, as Darwin postulates, actually occurs?

Apparently E. Ennert, Ph.D. didn't get out much. My cat ate all the chipmunks, moles, mice, and even rabbits in the neighborhood. Only the Grey Squirrels survived.

2. Can the origin of adaptive structures be explained on the ground of their _utility_ in this struggle?

He seems to argue that if there any features of any organism anywhere that can't be explained, that the theory must be wrong. But Darwin also talked about sexual selection and other factors that are conveniently forgotten.

3. Is there any reason to believe that new species may originate by the accumulation of fluctuating individual variations?

There is now, of course, with genetics, evidence down to the molecular level. But there is also considerable variation in just siblings, available to the author.

4. Does the evidence of the geological record--which, as Huxley observed, is the only direct evidence that can be had in the question of evolution--does this evidence tell for or against the origin of existing species from earlier ones by means of minute gradual modifications?

He uses this question to launch an argument of the gaps. If you have two fossils A and C that differ, then where is the intermediate form? When such a form B has been found, the argument now asks for two new fossils: one between A and B, and one between B and C. But even Darwin suggested that the intermediate forms would be very rare. And rare they are, though certainly non-zero. There is also evidence for speciation among living creatures, plants and animals.

So that's the first ten percent of the book. It continues on in a meandering manner. It continues to using logic that is frustratingly close to correct while consistently missing the mark. It is not much fun to read. I'd much rather read up on a null result experiment.

OK, so E. Ennert, Ph.D. was biased going into the work. And so was i. I owe a considerable amount to Darwin. If Evolution didn't work, then modern antibiotics wouldn't work. Without modern antibiotics, modern surgery wouldn't work. Without modern surgery, when my gall bladder ruptured and became gangrenous, i'd have died a painful death. Clearly, it's time for a prayer of thanks to God for Darwin.

No comments:

Post a Comment